Is Remote Working Shaping the Future of Work?

Foreword

Since the beginning of 2020, we have been facing a situation that never occurred before. The global pandemic has turned things upside down and forced us to find new reference points. First and foremost however, the crisis has been a crisis for us as people. All of the Orange Group’s teams have shown extraordinary willingness and adaptability to maintain a service to our customers at the same time as keeping fellow workers protected. This is a great source of pride for us.

It has been possible for large numbers of employees to work from home over long periods, even where they hold positions for which such an arrangement wouldn’t previously have been considered appropriate. This has been achieved while ensuring the necessary support for our customer-contact teams. Before the crisis, remote working was already part of working life at Orange, so the situation was not something we were entirely unprepared for. A first agreement on remote working was implemented in 2009 and 39% of Orange’s workforce in France was working remotely on a regular or occasional basis by 2019 .

Covid-related constraints have meant that the collective experience of working from home has taken on an entirely new scope and nature. It has greatly sped up the adoption of new ways of working, new digital tools and new ways of leading teams (our managers and employees have shown a great capacity for innovation in maintaining links and team dynamics and in ensuring both the welfare of fellow workers and the successful pursuit of work activities and projects). We are stronger for having faced this challenge together and learned how to turn it into a positive experience.

To get ahead of the learning curve and understand lessons learned and the place of remote working in tomorrow’s practices, the Orange executive committee initiated an innovative internal think tank process in July 2020. This process aimed to help us project ourselves into a future in which we hope to fully regain freedom of movement and choice. It mobilised more than 70 employees from all geographies, cultures, professions and generations of the group. It was conducted 100% remotely, thus removing all the usual boundaries to such a reflection. Similarly, consultation took place on these themes with employee representative bodies, and we also drew a lot of inspiration from the discussions and work carried out with the “Chaire Futurs de l’industrie et du travail” (Future of Industry and Work Chair) at Mines ParisTech PSL on the theme of remote working design.

This process has led us to the conclusion that, in the future, remote working will remain one of the usual modes of work at Orange and will be intrinsically part of our collective practices, our management models and, while making up varying proportions of working time, open to a greater number of types of job positions. The Orange “office” of the future will above all be a locus for relationships, teamwork and services: workplaces and spaces open to all employees, designed to support cooperative effort and nurture a sense of belonging to the company.

There will be a before and after in our relationship to the workplace: the world of 100% on-site work on the company premises seems to be over, as is the world where the same organizational structure is applied across all teams. In the future, the company will require a new level of flexibility, and this is also something that employees will ask for. We are moving towards models for which there is a different on-site/remote balance, depending on the job, but also most certainly depending on the time of life of employees, or where they are in their career path (for example, more time in the office when starting a job or when knowledge and know-how need to be passed on before retirement etc.). These new on-site/from home balances will also offer opportunities to meet our goals in favour of diversity and for an ever better integration of disabled people.

In terms of the challenges facing us, maintaining togetherness at work, social ties, calibrating each individual’s working experience and mitigating the new psychosocial risks relating to these developments, are certainly among those that will require the most investment. Supporting employees and managers is essential: helping them to define new team rituals, new balances, supporting them in designing the work experience within their teams and the company as a whole.

The book you are holding in your hands is, in this sense, a remarkable tool for laying the foundations, in each company, for the process of reflection that needs to take place. In a single volume it addresses all the areas to be taken into consideration and provides useful reference points for each organisation to help it to define the path it wants to follow in drawing the contours of the future of work.

Gervais Pellissier

Orange

Executive Vice President, People & Transformation, Chairman of OBS

Disclaimer

For this study, the authors relied heavily on the work and sessions of the ‘Remote Work’ group, organised by the “Chaire Futurs de l’industrie et du travail – FIT2” (Future of Industry and Work Chair) at Mines TechParis PSL, at the request of some of its sponsors. This work was complemented by extensive documentary research.

The resulting study, as well as any errors that may remain however, are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not imply any endorsement or approval by the sponsors of the Chair or by any of the organisations mentioned.

All persons involved in the preparatory work are mentioned in the acknowledgements.

Executive Summary

Despite peculiar conditions, the year 2020 has served as a laboratory for the practice of remote working on an unprecedented scale. This massive experimentation has had the merit of dispelling many preconceived ideas on home working but has also illustrated its limitations. At a time when companies are preparing for a return to work in the context of a “new normal”, what lessons can we draw from the experience and what points require closer attention? What does 2020-2021 tell us about the future of work?

Rather than villages of digital nomads, with blue lagoons and infinity pools, this empirical study is mainly focused on remote working “here and now”, i.e. on the democratisation (albeit partial) and eventual conditions for the extension of a mode of working that has long-since been desired by many and that has suddenly opened up for jobs and people to whom it was previously refused. In this respect, the study also offers some pointers to more radical developments, based on a few examples of forward-looking companies, mainly from the digital sector.

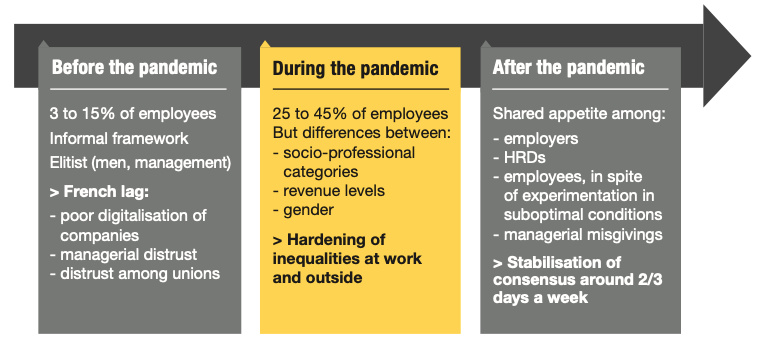

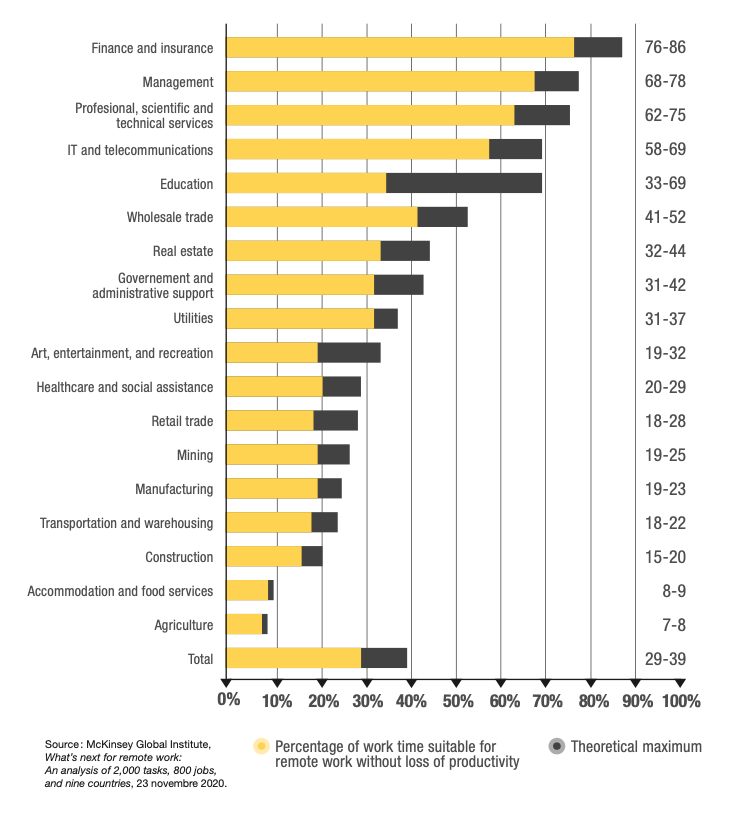

Historically, working from home has been viewed with suspicion both by managers and by trade unions. It has mostly been the preserve of senior managers (elitist telework) and certain “tertiarised” sectors of activity (banking and insurance, IT, scientific or intellectual professions), or it has been conceded sparingly as a “social benefit” (a perk), which did little to give it a good image. In fact, in 2019, there was still a great deal of inequality of access to remote working in France, Germany or Italy, showing a certain delay in the adoption of this practice compared to other OECD countries (Scandinavian countries, Netherlands, USA, UK), even though such comparisons can be subject to numerous statistical biases. The practice of working from home has however been increasing steadily since the beginning of the 2000s, in response to a persistent demand from employees in certain groups, particularly young people, women, and employees of large companies. The pandemic suddenly forced categories of the population who had never had access to remote working to work from home and thus contributed to a substantial change in perceptions. Remote working is however still unequally distributed: according to the French national statistical office, INSEE, 58% of executives and middle-ranking positions worked from home during the first lockdown compared to 20% of those in non-managerial roles and 2% of manual workers.

In the first quarter of 2021, two thirds of CEOs gave their seal of approval to home working, although with marked differences between big company bosses (and Tech employers) and SMEs. About 50% of HR managers are following their lead and making home working a permanent option. On the employee side, satisfaction levels have dropped, but remain high (around 75%), with notable differences depending on age, socio-professional category, and location. The length of the pandemic, restrictions on social activities, the periods of social isolation and the incessant changes in rules and instructions all no doubt contribute, more than just remote working itself, to the weariness expressed by some people, particularly younger employees at the beginning of their careers who are often poorly housed in big cities and eager for social interaction. Managers, a category initially reluctant to work from home, say they didn’t receive much support from their superiors during the ordeal and 25% of them are reluctant to make such a situation permanent, although they recognise some benefits.

In fact, the ILO, Eurofound and the OECD all predict that by the end of the pandemic period, remote working will have increased in comparison to previous practices, giving us a hybrid form combining on-site and remote work. A consensus among managers, HR directors, non-managerial employees and even academic researchers seems to have been established at around 2 to 3 days of remote work per week, with the exact proportions being set by each company depending on its sector of activity, strategy, company culture and other constraints, as well as employee aspirations. Around this new and evolving “social norm”, certain “ecological niches” are likely to develop, with more traditional operations on one hand and avant-garde companies going “full remote” (some digital companies as GitLab or DOIST for instance) on the other.

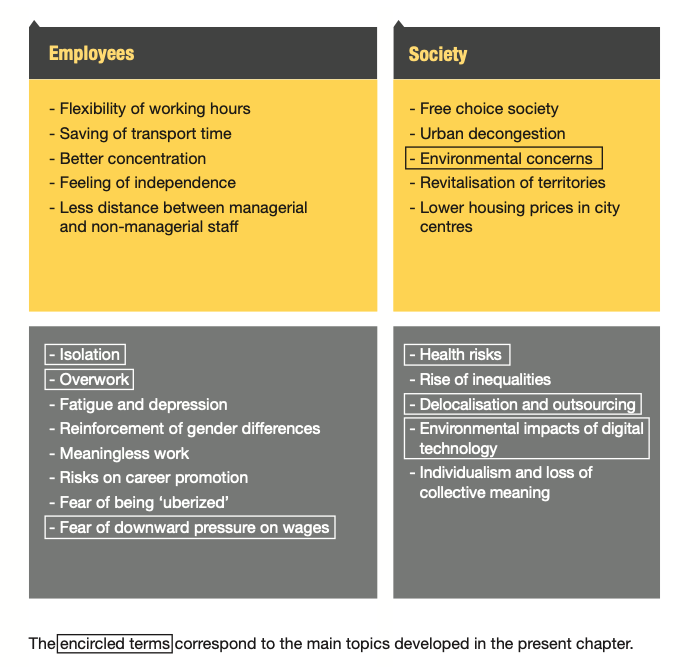

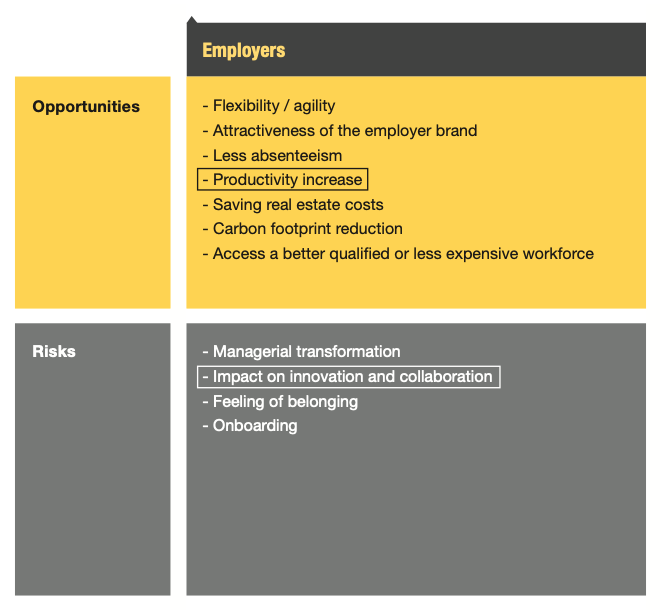

From the point of view of both employers and employees, the expected benefits of remote working remain broadly the same as they were before 2020-2021: greater flexibility, lower real estate costs, and attractiveness of the employer brand for employers; better time balance, less stress and commute time and greater independence for employees. Large-scale experimentation with remote working seems to have revealed new opportunities for employers however (increased productivity, speeding up of digitalisation, potential for hiring a more qualified or cheaper workforce, reduction of carbon footprint), while, on their side, employees have discovered some of the negative aspects of home working that had not been understood before (inadequate work space at home, isolation, overworking, erosion of social time, increase in health and safety problems, remote surveillance, additional costs). In fact, both the negative and positive aspects of remote working have been pushed to the extremes during the pandemic. It has often been at a rate of 100% and taken place in an anxiety-inducing and constrained context. We must therefore be cautious about the lessons learned, both positive and negative, from a remote working context that was forced on us rather than one that was chosen and whose deployment could be controlled.

Many issues related to remote working are still being debated after the 2020 experience. What is, for instance, its true impact on productivity? The effect seems positive, but this could be due to overworking on the part of employees. What are the effects on innovation and the creativity of teams? Results appear mixed. What is the lasting impact on the environment? Encouraging despite possible rebound effects. What are the consequences on companies’ salary policies and the job market? Downward pressure on wages cannot be excluded over the long term. What is the impact on social cohesion and inequalities? The contradictory arguments put forward on these questions are presented in this study.

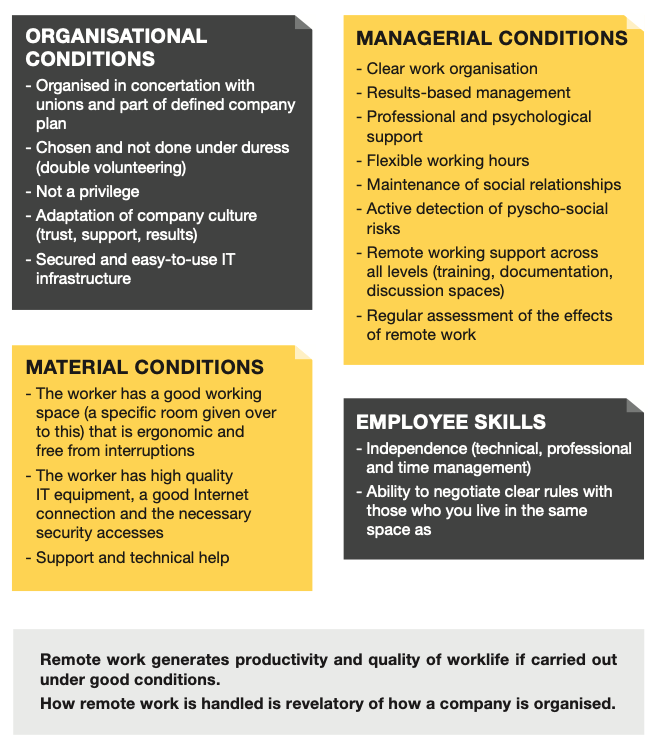

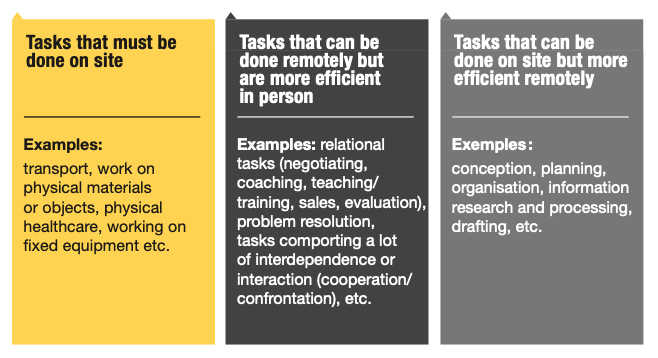

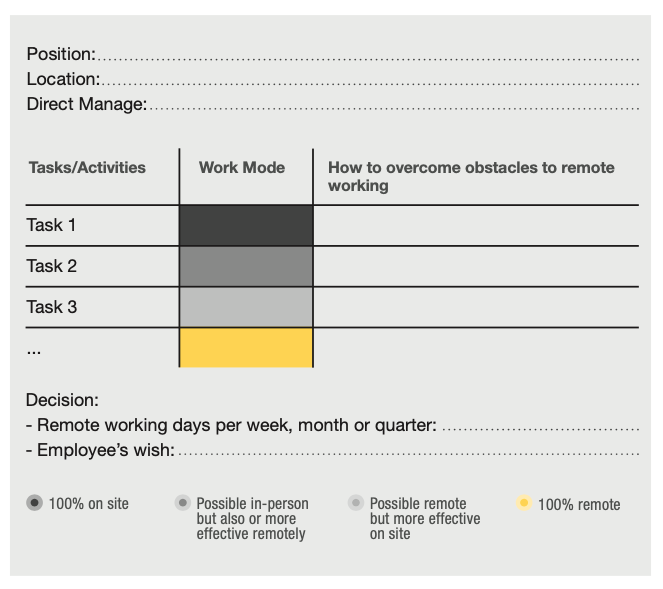

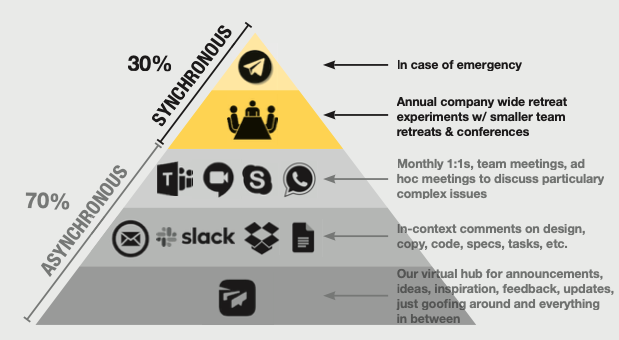

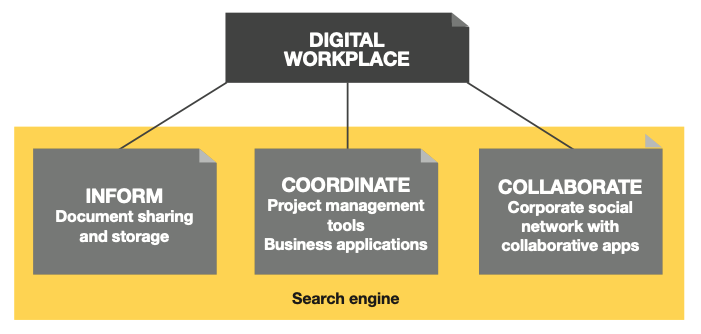

At a time when negotiations on new remote working agreements are underway in many organisations, it is important to focus on deployment conditions that are beneficial to all, which was not the case during the 2020-2021 experiment. Such conditions are now better understood. They are at once organisational (negotiation with employee representative bodies, remote working included in company plans, trust between people), material (furniture and computer equipment, good Internet connection, advice on ergonomics), managerial (clarity of work organisation, results-based management, professional support management) and personal to the employee (skills, professional independence, family situation, type of housing, etc.). This study successively investigates i) conditions of eligibility for remote working, which should in the future be conceived on the basis of tasks rather than jobs so as to ensure greater equity of access within the framework of a qualitative professional dialogue ii) the “multiplicity of legitimate workplaces”1 and the respective advantages and disadvantages of the home, the reinvented office (“flexible”, “dynamic” and even “distributed”) and co-working spaces iii) working hours and the effects of synchronous or asynchronous activity and iv) the gap between the growing sophistication of digital tools and the cultural and organisational obstacles that remain in the appropriation of new uses. Ultimately, this analysis provides answers to questions that many companies are asking themselves. Which activities should people return to the office for? How can chats around the coffee machine be reinvented remotely? What organisational or communication processes should be used to innovate and coordinate remotely?

Remote working has the great merit of putting the organisation of “real” work back at the forefront of concerns. Workforce representatives obviously have a key role to play here: whatever their previous reluctance towards remote working was, they must seize the opportunity to think deeply about the organisation of work and quality of life at work (on-site and when working from home) and bring up to speed their own communication practices with the use of digital tools.

Despite what we experienced in 2020-2021, managerial and organisational practices in companies have not deeply changed. At the very most their weaknesses or strengths have been revealed. Where management was previously control-oriented, this tended to be accentuated with home working; and where managers were already operating on the basis of trust, delegation of responsibility and independence have been reinforced. Remote working is also seen by many top managers in groups as a way to accelerate the managerial transition and the “cultural paradigm shift” they have been calling for, coupled with the digital transformation and adoption of new working methods (agility, flexibility, collaboration, logics of sharing, etc.). They have therefore seized on it as an opportunity with the potential to be instrumental in bringing about change.

More positively, remote working represents a unique opportunity to switch from a prescriptive form of management to results-oriented support. Above all, home working during lockdown revealed a need for better management: there is a real return to expect from investing in middle management, whether through traditional training, personal development, coaching, communities of practice or discussion spaces. It’s about making management methods more flexible (with a certain amount of the necessary letting go), while at the same time restructuring and reinforcing information and organisational processes. However, trends in France are rather the opposite: management is too heavy-handed and too ambiguous, i.e. heavily focused on micro-management but poorly invested in understanding real work, in explaining what is expected, in reducing “irritants”, in defining clear and shared operating procedures and purely and simply in team leadership. Remote working offers the opportunity to correct some of these shortcomings and to apply these lessons to traditional on-site working situations. New codes of communication and organisational methods could help us define the future of remote working and, more broadly, the future of work itself.

Introduction – 2020, the Big Shift

In a year of crisis, 2020 has left us with a host of new words to designate new realities: “Covid-19” and “Coronavirus” of course, as well as “social distancing” and “the new normal”. There are also words that we already knew, but which have taken on a new dimension (for example “virus”, “vaccine” or “mask”). The same goes for “working from home” which clocks up more than 76 million hits on Google search. What has happened? Has the era of remote working begun? What does the year 2020 tell us about the future of the organisation of work and lifestyles?

This study analyses the concrete manifestations of the phenomenon. Under the pressure brought about by the public health crisis, a very significant part of employees who had not previously been given the option of working from home abruptly switched to this mode of work for either all or part of the time. The lessons learned from this unprecedented situation tell us how to prepare for a “return to normal”, in which remote working will take a different, more sophisticated, form . In most cases, it will develop into a hybrid (or sporadic) form which will present us with new challenges.

For some time, remote working will continue to be unequally distributed across sectors of activity, jobs, and people. One of the major challenges for the future will be to widen its scope and to reduce inequalities of access, for example through digitalisation and professional dialogue on tasks, so as to make it possible to work at home on activities that were not previously eligible to home working.. Like any crisis, the Coronavirus crisis has created opportunities and sped up certain processes, which lead to new forms of organisation and management and whose limitations and risks must also be assessed.

Working from home or remote working?

A preliminary semantic clarification is necessary. While the term “working from home” (or WFH) is the most commonly used, it does not, in our opinion, cover all the aspects of the phenomenon nor does it fully illustrate its complexity.

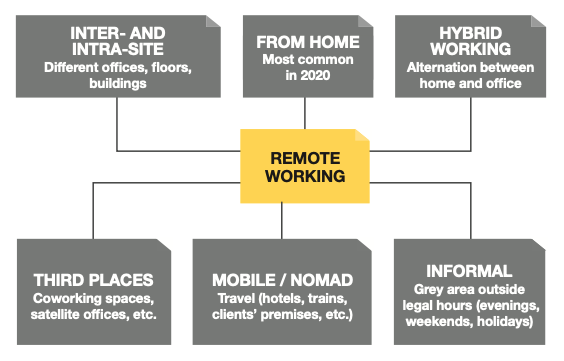

“Remote working” has multiple forms (see chart below): inter and intra-site remote teamwork (in different offices, floors or buildings); activities performed mostly at home; alternation between work at home and work on site (known as “hybrid working”); ongoing work or one-off jobs in dedicated third places (telecentres, satellite offices, coworking or corpoworking spaces), usually closer to the worker’s home; mobile remote working, which involves travel, combining various locations (worksites, hotels, client premises, transport, etc.) and informal remote working, which again takes place in various places (home, hotels, transport, client premises, etc.) but mostly outside legal working hours (evenings, weekends, vacations).

Therefore, even if we sometimes use the terms “working from home” and “remote working” interchangeably in this study, we conceptually prefer the latter as it better encompasses the blurring of time, space and status markers generated by these forms of work and is better suited for describing (even vaguely) the contours of the future of work.

Chart 1.1 – The multiple forms of remote work

These new forms of work organisation have the particularity of breaking, in whole or in part, with the three units (of time, place and action) that have long defined corporations, as well as with three fundamentals of salaried work (hierarchical relationships, group work time, located work groups). The rapid expansion of remote working is blurring the boundaries that previously defined both “normal” work and the corporation, which have, in any case, already been challenged by heterogeneous wage arrangements (short contracts, temporary work, “bossless” employment), alternative forms of work and employment (economically dependent freelancers, partners/consultants working on company premises) and the extended enterprise (suppliers, subcontractors located all over the world).

Employers concerns

This study was born out of a request made by the sponsors2 of the “Chaire Futurs de l’industrie et du travail – FIT 2 ” (Futures of Industry and Work Chair) at Mines ParisTech PSL, who set up an ad hoc working group on the subject of remote working. Remote working during lockdown was carried on a large scale and in suboptimal conditions. Organisations were taken by surprise, whatever their previous appetite for or maturity in respect of it. The situation therefore calls for a reflection on how to return to work in the context of the “new normal”, which is bound to emerge as profoundly different after this unprecedented experience. At the same time, the legal obligation to negotiate this new normal with employee representative bodies means that there will doubtlessly be a great deal of manoeuvring with respect to remote working, requiring human resources departments to have examined the subject from every possible angle, taking into account the risks that transpired during lockdown (physical and psychological health, isolation) as well as the opportunities it offers (new managerial relations, flexible working hours, accelerated digitalisation, reduction of workspace, etc.). In some large groups, the senior management has asked real estate departments to carry out a rapid assessment for the redesign of workspaces and workplaces, to grasp opportunities to reduce real estate costs without affecting productivity or quality of life at work – the time lag between decisions and implementation on real estate projects means that a detailed roadmap has to be drawn up. Digital transformation managers have been asked to assess how remote working and digitalisation can come together to offer the increased flexibility and agility that can be achieved when these two developments are well-combined. Obviously, managers are among the most impacted, as remote working implies a redesign of their role itself and their managerial style. Particular attention shall be given to managerial transformation in connection with all the above questions. More broadly, the issue of remote working is something that needs to be considered alongside other strategic corporate challenges, particularly in terms of corporate responsibility (social, societal, environmental, and economic).

However, even though the programme was already quite substantial, the sponsors did not wish to confine the project remit to these short-term, situational aspects. They were all aware that remote working raises longer-term questions regarding company boundaries and the integrity of employee groups, the organisation of work, independence, responsibility, the direct and indirect participation of workers and CSR policy. It also raises political, social and societal issues (lifestyles, land use planning, urban planning, housing policies, social and wage policies, environmental policies, etc.). A link was thus clearly established by the participants into the working group between remote working and the “future of work”. Indeed, some of them were already engaged in a consideration of prospective impacts on the subject.

The present study is founded on working group discussions, interviews with experts and witnesses (sociologists, HRDs, managers, planners, etc.) carried out between December 2020 and March 2021, and on an extensive documentary research drawing on the large number of surveys and polls carried out during the period and on institutional reports and academic articles on related topics and across a wider time span. It is also based on previous research by the FIT 2 Chair and La Fabrique de l’industrie about changes in patterns of work3 , organisational models to promote employee independence and responsibility4 and quality of life at work5 , and work design6 .

While this study takes remote working as a starting point, its primary objective is to provide reference points and areas for vigilance for companies that wish to reassess their working organizations in the light of the lessons of 2020-2021.

The Adoption of Remote Working: Past, Present and Future

The multi-faceted nature of “remote working”7 and its numerous manifestations, both nationally and internationally, makes it difficult to audit but because of the lockdowns that took place during the pandemic, 2020-2021 does nevertheless represent a pivotal date in its history. Used selectively both by employers and employees prior to Covid-19 and often managed on a case-by-case basis, workers in France and everywhere else in the world suddenly had no choice in the matter, blurring perceptions. Remote working was introduced to large sections of the population and to types of jobs that had previously been unaffected by, or even been perceived as incompatible with it and this made the last years a watershed in terms of its deployment.

Before the public health crisis

Promoted since the 1970s in developed countries, remote working was initially seen by public authorities as having the potential to influence regional planning (opening up rural areas, better distribution of the population, public infrastructure planning)8 and attenuate some of the downsides of indus trial and urban society. These arguments were only modestly received however. Twenty years on, the European Commission was supporting remote working with white or green papers, identifying it as a way of contributing to the development of the information society it was calling for. Later, working from home became part of the vision for the ecological transition but it was never examined as a central issue in itself. It was part of an overarching, more generalised analysis, “companies and individuals only being components of much larger systems”9.

Nomads and sedentary jobs: remote work in the context of globalisation

It was really only with the extension of economic globalisation and the widespread adoption of information and communication technologies (ICT) that companies would start to see remote working as a way of increasing the mobility and fluidity of labour, while reducing costs.

On an international scale, remote working became a component of delocalisation solutions and the outsourcing of work as a new practice to help coordinate and link remote teams inside or outside companies, supported by telecommunications, IT and then digital resources: developers in Ban galore, traders in New York, call centers in Madagascar, R&D centres in Europe, factories in China, etc. In 1976, J. Nilles already defined “telework” as the substitution of telecommunications for the trans portation of goods and people10. In this respect, remote working is not new but is a firmly established reality that has been steadily gaining ground since the 1990s. It is one of the components in the way companies present themselves as flexible, mobile and open to the world.

According to the distinction put forward by Pierre-Noël Giraud between nomadic and sedentary jobs in the context of international competition11, we can say that international remote work has essentially been the domain of “nomadic” jobs (even if the people who hold these jobs never leave headquarters), i.e. creators and pro ducers involved in the production of goods and services that can be exchanged across borders, and whose jobs are highly exposed to international competition and are fully integrated with ICTs (innovators, creators, designers, traders, developers, etc.). On the other hand, so-called “sedentary” jobs, in sectors less exposed to globalisation and often less digitised, were far less affected by international remote work. Symmetri cally, nomadic jobs have also corresponded to better-paid jobs.

Gradually, remote work began to change in scale and claim a place at local level (“tele commuting” or “working from home”), but it continued to be perceived by companies as the domain of executives and qualified experts, while “sedentary” employees tended to be associated with the negative aspects of working from home (need for control, isolation, lack of digital skills)

2020-2021 marked a break in this segmentation, bringing an unprecedented mass of so-called sedentary jobs into the realm of remote work.

Remote working in France

In France, before the pandemic, remote working was often something that was adopted as an optional solution by employees and employers who saw the mutual benefits it offered.

For the employer, these were mainly more flexibility, less absenteeism, the opportunity to allow employees to juggle social time more freely and thus attract and retain them, the reduction of transportation risks and lower office rental costs. However, many employers were still fearful and suspicious of the impact on productivity and the personal investment of remote workers.

For employees, remote working offered valuable savings in commute time in large cities, greater freedom in the management of social time (domestic and professional) and schedules, and the benefits of a less vertical management mode. At the time, it was mainly of interest to “younger em ployees, but also to older workers (55 and over), who appreciate the reductions in commute times and are less concerned about needing to show their faces at the office to qualify for possible promotion”12.

Home working is also of interest to governments, who see it as a way to address en vironmental issues and combat urban congestion and the costs associated with the constant renovation of busy roads.

In the 2000s, the psycho-sociologist MarieFrance Kouloumdjian underlined the “ex perimental, one-off, isolated, piecemeal, reactive nature”13 of many of the decisions relating to the adoption of home working and the fact that they were generally made n response to individual situations, whereas for her, remote working was related to im portant technological, organisational and social issues requiring overall consistency. She criticized the predominance of a “small steps approach over strategic management”14.

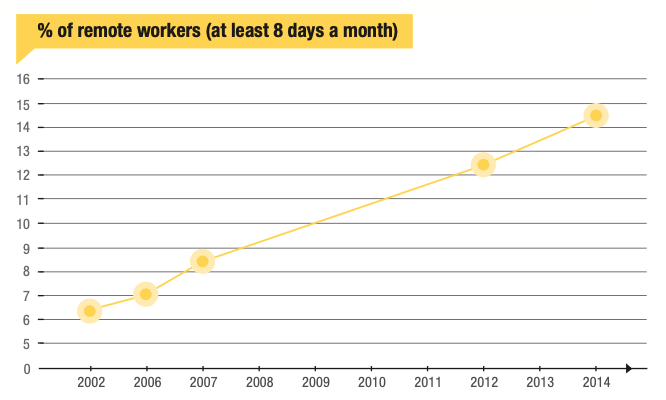

However, remote working in France continued to grow, as shown in chart 1.215, but at the same time with a certain “French lag”16 compared to other OECD countries. In 2017, in France, the share of remote workers was estimated to be between 3% and 15% of the working population17, depending on whether only formal remote working was taken into account or whether occasional and informal remote working was also included. By comparison, the figure was about 30% in Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Sweden, Finland), the Netherlands and the USA18 – the statistical consistency of these comparisons is not always perfect, due to the diversity of definitions of remote working taken into account.

At the time, several factors were put forward to explain this lag in France: a lower level of digitalisation of companies, but above all the “cultural specificity of French management styles which [saw] a possible risk of reduced personal investment and loyalty among employees, or, from the point of view of trade unions, possible negative effects in terms of increased workload and the risk of destroying the social aspects of working life”19. Remote working was often seen as a “perk”, especially for women, conflating it with part-time work and therefore tainting its image.

Modest but real, the movement towards remote working did indeed exist in France before the years 2019-2020, when both the big transport strike at the end of 2019 and early awareness of the pandemic from March 2020 had their effect. Gradually, time at work became just one of the components of working time.

Chart 1.2 Share of remote workers in France from 2002 to 2014

Source: Gartner, analysis by Roland Berger and LBMG Worklabs (data from 2014), cited in Dortier, 2017.

During the public health crisis (up to March 2021)

During the first lockdown in France (from 17 March to 11 May 2020), the govern ment imposed 100% home working, on a large scale, in a hurry and without any negotiation or prior preparation. At the end of March, DARES (the French national directorate for research, studies and statistics) estimated a quarter of employees were working on site, a quarter were working at home, a quarter had been put on the short time working scheme. The remaining quarter were on sick leave or taking time off for childcare, on vacation or had been forced into unemployment20. So about 75% of employees were at home, but not all of them were remote working. The proportion of people doing 100% remote working was particularly high in banking and insurance (45%), IT (41%) and publishing (40%) – a remote working pattern that was already in evidence prior to lockdown.

Unequal working conditions during lockdown

According to the French national statistical office, INSEE, 58% of managers and middleranking occupations worked remotely during the first lockdown, compared to 20% of nonmanagerial employees and 2% of manual workers21. Another survey conducted over the same period showed that 70% of those who worked remotely during lockdown were managers or in middle-ranking occupations, while 61% of on-site workers were bluecollar workers and non-managerial employees22. Remote working was already predominantly the domain of managers prior to lockdown (61% of remote workers in 2017) and was very elitist (mainly men with positions of responsibility and high level of education), even if it also involved low-skilled office jobs, sometimes less secure self-employed workers and subcontractors in low-cost countries.

Remote working practices during the first lockdown thus confirmed the major differ ences that previously existed within the French working population in this respect: those between socio-professional categories (blue collar, white collar), sectors of activity, income levels (21% of the lowest-paid remote worked compared to 53% of the highest-paid23) and genders (men and women).

Broader adoption was a leveller

The extension of remote working during the first lockdown did however serve as a leveller, with the proportion of upper so cio-professional category workers working remotely falling from 65% in 2019 to 59% in April 202024. 44% of remote workers in the first lockdown were experimenting with this form of work for the first time (first-time users) and 75% of them were experimenting with it for the first time at 100%25. Among these new users, a large proportion were in jobs previously considered incompatible, either partially or fully, with remote working.

This first lockdown also led to a broader adoption of remote working among women, who made up just 38% of remote workers in 2019, compared to 44% during the first lockdown. Women thus made up a higher proportion of the new first-lockdown remote workers (52%26). However, remote working conditions among women were far from optimal, as only a quarter of them had a dedicated and separate working space (against 41% of men)27.

Women and remote work: specific risks28

• 1.5 times more likely to be frequently interrupted than men.

• 1.3 times more likely to experience anxiety at work than men.

• Only 60% of women in the private sector have confidence in their professional futures, which is 15 percentage points lower than men.

• During videoconferencing, women find it more difficult to speak up and get their ideas across. They feel less effective.

During the second lockdown (from 27 Oc tober to 15 December 2020), government instructions were much more flexible, not to say vague. However, remote work was once again widely used, with 45% of private sector employees working from home, 23% of them full-time29.

There was a tailing-off at the beginning of 2021 however. At the end of 2020, only 31% of employees were working from home full or part-time (62% in banking/ insurance, 62% in services, 23% in the health sector, 19% in the retail sector and 17% in industry)30, forcing the government to remind the French employers of their obligation to use remote working wherever possible to contain contamination, under penalty of sanctions or public disclosure (name and shame).

Meanwhile in Germany31

According to a survey of 7,677 workers conducted by the Hans-Böckler Foundation, published on 21 April 2020, the rate of those who remote work most of the time has increased from 4% to 27%. In 2016, 9% of employees were working from home on a rotating basis (often one or two days per week) or all the time. During the pandemic many employees were thus experimenting with working from home for the first time. More than half worked at companies that did not have any rules or arrangements in place for remote working.

For many years, the biggest obstacle to working from home was the mistrust of employers and their fear of losing control. A survey conducted by the WZB (Social Science Research Centre in Berlin), during the week of 23 March to 5 April 2020, among 6,200 working people, showed that remote working was mostly the preserve of people with a university degree (20 percentage points higher than those without a university degree). This privilege was related to the type of activity and to the so-called “independent work organisation skills”. Respondents in lower-wage categories and the self-employed were more often forced to stop working. In Germany, there is still resistance to the “right to work remotely”, as proposed by Labour Minister Hubert Heil (SPD). Employers remain firm on the issue and have been rejecting all such proposals for years.

While the number of remote workers has fallen since the beginning of the crisis, the number of days worked at home remains well above the pre-pandemic average: 3.6 days per week vs. 1.6 days per week at the end of 201932.

The decline in remote working from the end of 2020 to 2021 seems to be linked to two concomitant phenomena: strong pressure from management to return to the workplace, but also the fact that employees have become fed up with the situation, especially those who live alone in small spaces where they do not have a dedicated workspace allowing them to separate off their work from other activities. As a result, it is above all young people who have grown tired of working at home. 26% of remote workers also feel that working from home has an impact on their psychological health33. Many experts point to the phenomenon of psychological exhaustion, blaming home working as the main source of this. But there are other situational factors at play as well: the length of the public health crisis, the constraints associated with it (curfew and closure of all social life / entertainment sector activities) and the constant changes to government directives, which generate anxiety, uncertainty and fatigue, all contributed to this psychological exhaustion.

Towards hybrid work

The experiences of 2020-2021 seem to have profoundly altered perceptions of remote working.

HRDs. Following the first lockdown, 85% of HRDs wanted to expand remote working and 82% were considering increasing the number of positions eligible for remote working34. On the eve of the second lockdown, enthusiasm seems to have waned somewhat: only 50% of them then considered it desirable to make working from home permanent. There are still concerns about the impact of remote working on employee engagement and feelings of belonging.

Senior executives. In January 2021, 67% of CEOs were still in favour of remote working in their companies35. However, the level of their enthusiasm depends on the type of their companies. While bosses of international corporations and tech companies say that they are keen on seizing the opportunity of changing work practices in the light of the experience they have gained, bosses of SMEs are much less favourable, with 84% saying that remote working undermines team cohesion and increases the risks of isolation of employees36. Only 23% of SME bosses say they want to make home working permanent, compared with 80% of CEOs in large companies, mainly because of their lower level of digitalisation, but also because of an organizational structure that is less suitable for teleworking.

Managers. Another novelty in 2021 is the divergence in perception between senior executives and managers regarding remote working. While two-thirds of senior executives are now in favour of remote working, the share of managers in favour of working from home has dropped over the last couple of years, from 55% in 2018 to 50% at the end of 2020, and nearly a quarter of them now say they are against home working. Managers are exhausted and only one-third (32%) say they have received support in implementing remote working. Despite these difficulties, they still recognise the following benefits: greater team autonomy (51%), lower absenteeism (35%) and greater employee satisfaction (33%)37.

Non-managerial employees. Satisfaction with home working has declined among non-managerial employees but nevertheless remains high. All surveys show a high level of satisfaction with home working during lockdown, despite suboptimal conditions. However, there are differences between employee groups according to age, socio-professional category and geographical location, as highlighted by a study from the Workplace Management Chair at ESSEC Business School38.

Differences according to age. Remote work is more popular with millennials (born between 1978 and 1994) and Generation Xers (born between 1965 and 1977), 79% and 72% of whom respectively wish to work remotely. Then come Generation Zers (born after 1995) and Baby Boomers (born 1945-1964) with 68% and 67% wanting to work remotely. The lower appetite for home working among Generation Zers may be due to the fact that, as the youngest genera- tion, they are at the very beginning of their professional careers, still live in modest housing or even under difficult conditions and aspire to a strong social connection with peers. As for the baby boomers, they are at the end of their careers, probably find it more difficult to change their work habits and are less comfortable with tech- nological tools.

Differences according to socio-professional category. 85% of senior executives and 82% of senior managers want to continue to work remotely, compared to 67% of nonmanagerial employees (with an overall average of 73% of respondents).

Differences according to geographical location. 83% of all employees in the Paris region want to continue home working, compared to 70% in medium-sized cities and 64% in small towns.

It seems almost certain that the use of home working will continue to increase following the pandemic. However, the differences between employee groups suggest that the impression of a general appetite for remote working should be qualified. The findings of sociologist Alain d’Iribarne also suggest that companies should introduce demographic, geographical and socio-organisational analysis when considering remote working implementation for the future: “Companies with employees with an average age of 55 years and 30 years of work experience in Taylorian and/or post-Taylorian organisations cannot be organised in the same way as those with employees with an average age of 30 and 5 years of experience in a ‘liberated’ work environment.”39 So, we need to be cautious regarding solutions that are too homogeneous, centralised and inflexible, which do not account for such differences. In this sense, we shouldn’t be too hasty in drawing conclusions from 2020-2021, a year that should be seen as exceptional and in which both the posi tive and negative aspects of working from home have been carried to the extremes by the anxiety-inducing context.

About 80% of those now working from home want to continue to do so. This feeling is more pronounced among managers (86%), women (80%) and employees of very large (80%) and service-sector com panies (83%)40. These cross-categories are the ones that will be the most active in bringing about a new social norm in work organisation. Between 2 and 3 days of remote work per week seems to be a consensus among senior executives, employees, trade unions and even… academic researchers. This hybrid solution seems to be what could become the new norm for work organisation. Like any norm, it will have to allow for deviations. It is likely that certain “ecological niches” will survive in the tail of the comet, with some companies maintaining “traditional” modes of organisation that will work very well. On the other hand, there will also be avant-garde organisations that go beyond the norm, up to “full remote” (100% remote working for all employees).

Back to the office: announcements criticized in the US

In the spring of 2021, many US companies seemed to take a step back on the issue of remote working. This was the case for banks and financial services companies such as JP Morgan or Goldman Sachs, but also, more surprisingly, for digital companies as well.

Apple: on 3 June 2021, Tim Cook announced the implementation of hybrid work starting in September and expected to continue until at least 2022 (he then plans to re-evaluate this “pilot” program): most employees will be asked to come into the office on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays and work from home on the other days, but others will be asked to come in 4-5 days a week. In addition to this plan, employees will also be able to ask to remote work for up to 2 weeks per year. This rigid plan was not well received by some employees: a Slack channel was launched on this issue which was then the subject of a letter signed by 80 employees. They encouraged Apple to be more flexible and ambitious in terms of home working. They point out that despite “the enormous constraints that have weighed on the company for over a year, Apple has continued to launch new products, hold events, introduce new operating systems and ultimately continue to achieve unprecedented financial results.” In conclusion, the authors of the letter ask for 5 points to be discussed:

• Give teams decision-making power over remote work (as they already have over hiring)

• Organise a large and transparent survey on this topic

• Address this issue in pre-departure interviews

• Communicate a clear plan for employees with disabilities who may be affected by a hybrid organisation

• Conduct an environmental impact study on the consequences of returning to the office.

Since then, because of the Delta Variant (but maybe also because of the social unrest among work teams), Apple has declared that office reopening is now planned for October 2022.

Ubisfot: In early June, Ubisoft’s HR department emailed employees, telling them that most will have to return to the office regularly, stating that “the office will remain a

central pillar of the Ubisoft experience”. Only a small number of employees will be able to remain entirely remote. Reactions were not long in appearing on internal forums

where messages like “We spend 90% of our time sitting at our desk with headphones on. I don’t see how there would be any more creativity with lots of people with head-

phones on in a small space.” Another developer notes that “In the meantime we released Valhalla working remotely” and another developer adds “As well as 4 seasons of Rainbow Six Siege… And the beta of Roller Champion… And Hyperscape…” Some people are already thinking of “leaving for a studio that offers 100% remote work”.

Amazon: as of March 2021, Amazon announced that it wants to “return to a culture centred on the desktop as a baseline”. An internal memo announced a return to full-time on-site work starting this fall in the United States. However, in June, the company changed course by offering a more flexible formula to its employees whose activities do not necessarily take place on site: it will be possible to work from home 2 days a week, or even more with the agreement of your superior.

In August 2021, Amazon ultimately announced office reopening for January 2022.

International comparisons on the prospect of work hybridisation

According to an ILO report41, it is likely that the proportion of remote work will increase as a result of the experience during the pandemic, in a mixed form combining on-site and remote work. Eurofound42 and the OECD43 report that the experience during the public health crisis will lead to an increase in remote work.

Initial research and surveys show that a very high percentage of workers would like to work from home more frequently, even after the lifting of the social distancing measures and even though they have experienced ‘from-home’ in an unpleasant and suboptimal way. 70% of the employees surveyed by Eurofound in July 2020 were satisfied overall with this experience. This figure rises to 80% in Canada and only 8% of Canadians aspire to return to the office full-time. In the UK, 68% of employees want to continue working at home after lockdown.

Employers are also showing an increased interest in ‘from-home’: 70% of UK employers would like to develop remote working on a regular basis and 54% of them on a full-time basis. EU companies expect that in three years’ time, 29% of their workforce will be working remotely and 39% of employers say they no longer care where work is done.

However, there is still a long way to go as 34% of employers surveyed in the EU still do not have a formal policy for managing hybrid working arrangements.

Remote working in France: Summary

Risks and Opportunities of Remote Work

While the dynamics of pre-pandemic re mote work (chosen optionally) were very different to those (mandated) of the pandemic, 2020 did allow us to test the advantages and disadvantages of this work mode on a large scale. This enabled a more objective analysis of its effects, helping to overcome certain beliefs (or prejudices) or, on the contrary, bring to the forefront certain realities in its regard. Above all, it demonstrated, step by step, what the conditions for “better” remote work might be, since these conditions were not gathered during the pandemic period.

The table 2.1 shows the main advantages and disadvantages mentioned by employers and employees. For both groups, the expected benefits remain more or less the same as before 2020. However, large-scale experimentation with home working also seems to have revealed new opportunities for em ployers44, with 64% of HR managers seeing it as a way to increase productivity and 61% as a way to reduce their carbon foot print. They also see it as an opportunity to access a more skilled or cheaper (23%) and more flexible (11%) workforce. For employees, while the appeal remains, the experience of 100% remote working also literally brought home some of its negative effects, which had not been perceived while it was still only being practiced partially or not at all.

Some of these opportunities and risks remain more controversial than others and the data and analysis do not all point in the same direction. This chapter focuses on these areas of debate, which deserve our attention in as much as they are likely to influence future collective bargaining. The circled terms in the table correspond to topics developed in this chapter.

Does remote work increase productivity?

Does remote work have a positive impact on productivity? This question is of primary interest to businesses. In the past, senior executives have tended to see a negative correlation here, but many seem to have changed their minds as a result of the 2020 experiment. Are there elements to back-up this change in attitude?

Studies on the impact of home working on productivity are highly contradictory, depending on which factors they focus on. Some look at overall productivity, taking into account savings in real estate costs, energy consumption and wage effects, while others emphasise the conditionality of gains depending on how remote work is implemented. In total, these studies show a range of impacts, from 20% reductions in productivity to 30% gains, so they would seem to be rather inconclusive.

Some studies, conducted before 2020, estimated that productivity gains from remote work could range from 5 to 30%, taking into account several factors including quieter working conditions (thought to facilitate concentration): “Many studies show that remote work reduces interruptions, distractions and the time needed to recover after work, and thus improves concentration, efficiency and quality of work, as well as performance.45” A recent memo from the Sapiens Institute46, citing a 2016 report by the firm Kronos, a specialist in labour relations, reports a 22% increase in productivity. These figures, however, which refer to old studies with sometimes uncertain methodologies, seem unconvincing.

Table 2.1 Summary table of opportunities and risks of remote work as perceived by stakeholders

Productivity gains at the cost of overwork?

In addition to improved concentration, work from home may also improve work productivity through increase in working time (overwork): the time saved in transport is largely used for professional activities; lunch breaks are shorter and other breaks during the day rarer. This increase in working time was documented during the first lockdown. An American study, conducted by researchers from Harvard and New York University47, analysed the e-mails and shared work diaries of 3.1 million employees in the United States, Europe and the Middle East over a period of sixteen weeks, including the lockdown. It revealed that work time increased by 48.5 minutes per day, or about 4 hours per week.

Some authors attribute the intensification of working time produced by working from home to the “social exchange theory”. Before 2020, remote work was seen as a privilege in many companies inducing a feeling of “accountability” in employees which translated into increased effort to fulfill their “debt”. Negative managerial representations of home working force remote workers to develop behaviours to remain visible within their work environments and prove that they are “at their desks” and working. For example, they make a point of being responsive to emails, instant messages or phone calls, which can add to their workload. These factors may have come into play in 2020.

A 17-month study48 (April 2019 to August 2020) on 10,000 professionals at a large Asian IT services company confirms the tendency to overwork: the number of working hours was off the chart, with total hours worked increasing by 30%, a majority of which (18%) were outside normal office hours. The originality and strength of this study lies in the objectivity of the analysis and monitoring data on which it is based. Many other studies simply ask employees about their subjective perception of their efficiency and productivity at work. The study also focused on a sector composed of highly skilled professionals whose work involves cognitive work, collaboration and innovation, where other studies have focussed on occupations with repetitive tasks (e.g. in call centres, see Bloom et al. below).

More surprisingly, despite this overwork, production remained stable. Employees thus worked more to achieve the same results: productivity would have fallen by about 20% eventually according to the authors’ estimates. To explain this paradoxical phenomenon, the authors of the study point to several factors:

Time spent in meetings (video conferencing) increased after the home working transition phase, suggesting a significant increase in remote coordination costs.

As a result, the uninterrupted hours spent in deep individual concentration decreased.

Internal (co-worker) and external (client) networking activities decreased, as did coaching and bilateral exchanges with supervisors.

These results suggest that while it was possible for companies to maintain their business activities in spite of the public health crisis, this was largely thanks to employees over-investment. The authors thus question the sustainability of this form of remote work. Their findings highlight the inflation of time spent in meetings to the detriment of individual concentration and networking activities, considered as fundamental variables of work productivity. Conversely, “working after hours and attending many meetings does not seem to contribute substantially to productivity”.

International comparisons on overwork

“Almost all national expert reports surveyed show that remote workers tend to work longer than the average employee in their respective countries.49” In Belgium, for example, a 2005 study found that remote workers worked an average of 44.5 hours per week compared to 42.6 hours for on-site workers. Similar results are given for Finland (2011), the Netherlands (2015), Spain (2011), Sweden (2014) and the UK (2012).

These findings were further verified during lockdowns: a survey of 1,000 workers from the UK showed that 38% of them said they were working longer hours50. Employees are far from being the only ones impacted however: in China, Microsoft calculated that the weekly workload of executives managing remote teams increased by 90 minutes due to individual and group virtual meetings.

Remote work conditions and productivity

In a study on home working at a Chinese travel agency (Ctrip) in 201551, researchers Nicholas Bloom et al. pointed out that its beneficial effects on productivity only apply when workers choose to work from home and are lost when they are obliged to do so: “At Ctrip, employees who decided to work from home were 13% more pro ductive than their colleagues. It should be noted, however, that only half of the employees volunteered. How would the other half have performed if they had been forced to work from home, as everyone is doing right now during the COVID-19 crisis? It’s hard to say.52”

Conversely, research conducted at CNAM and corroborated by ergonomists shows a loss of productivity in the order of 20% when remote working takes place on a full-time basis, with this loss even higher where remote working is carried on under bad conditions53. This is due to the “over time” required to learn tools, technical problems, digital (more emails, instant messaging, etc.) or household interruptions, losses related to the physical and mental health of employees (poor installation at home, social isolation, digital exhaustion) and losses related to the “lesser impact” of managerial instructions from a distance.

The impact of remote working on productivity is therefore thought to depend on whether workers choose it rather than having it imposed on them, as well as the conditions under which it is carried out.

Intensity of remote working and productivity

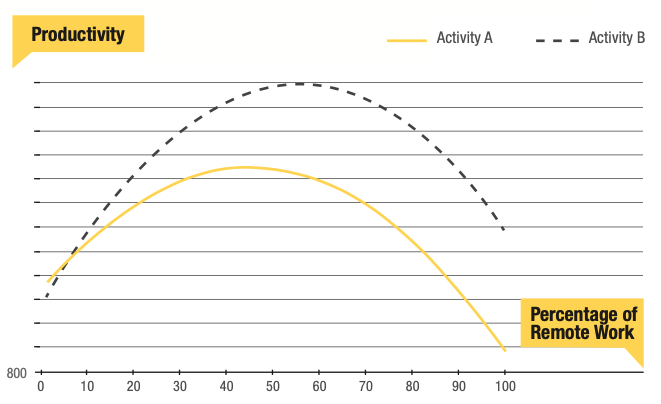

While the effects of from-home on productivity may therefore vary, agreement seems to be coalescing around the fact that in terms of productivity, optimal work is neither 100% on site nor 100% remote. Productivity decreases from a certain threshold of remote work and this varies according to sectors and professions. This is shown in the inverted U curve presented by Antoine Bergeaud and Gilbert Cette54 and adapted from previous work by the OECD55. “The efficiency of workers improves at low levels of remote work intensity but decreases when remote work becomes ‘excessive’. Thus, there seems to be an ‘ideal zone’, characterised by a certain intensity of remote work as a proportion of working time, where the efficiency of workers – and thus their productivity – is maximized, although the exact shape of the graph is likely to vary across sectors and occupations.”

Chart 2.2 Relationship between intensity of remote work and productivity: the inverted U-curve

Source : Bergeaud A., Cette G., « Télétravail : quels effets sur la productivité ? », Billet n o 198, , Banque de France, 5 January 2021.

The OECD cites the example of industries or occupations where the relationship between complex tasks and communication is so important that the optimal level of remote work is lower.

This analysis suggest that gains in productivity may be available if post-Covid re mote work deployment is better controlled.

Does remote working affect innovation and creativity?

One of the fears frequently expressed by companies is that from-home will have a particularly negative effect on innovation as well as on the creative impact produced by the informal encounters that occur when people share physical spaces. Despite the myth of the solitary entrepreneur (with renowned figures such as Edison, Ford, Jobs, Zuckerberg), it is actually difficult to in novate alone. Relationships only mediated by ICT are perceived as insufficient in this respect. Are these fears justified?

Economists Nicholas Bloom and Carl Benedikt Frey56 share these concerns and warn of a risk of innovation deceleration threatening economic growth.

For N. Bloom, his study on the Chinese travel agency showed that when workers choose to work from home there is a positive impact on productivity for repetitive tasks such as answering calls or making reservations, but a negative one for innovative creative activities. This is the most commonly-held view. However, exactly the opposite view is held by E. G. Dutcher57, who highlights the negative effects of remote work on productivity for routine tasks, but its positive effects when it comes to carrying out a task requiring some form of creativity, creativity being seen as flourishing mainly in quiet and solitude.

The OECD, for its part, makes the point that things are not clear-cut. Silicon Valleytype “clusters” in France “seem to provide a clear indication that sharing the same physical space is essential for innovation”58. Other work however indicates that as information sharing between remote workers becomes more widespread, “the more intensive use of remote work could become part of a larger reorganisation process, potentially conducive to efficiency gains made possible by the digital transformation.”

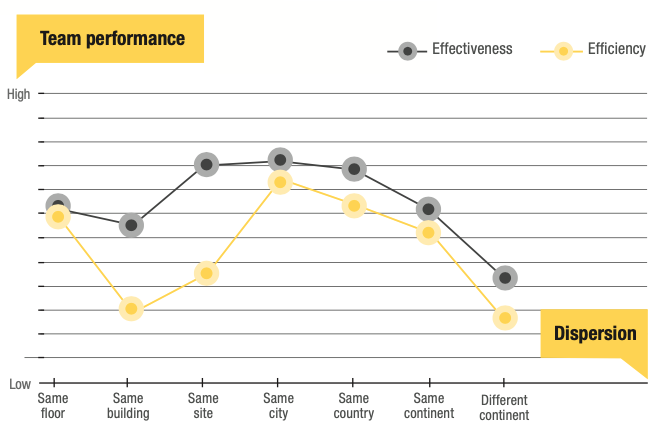

This second view is also held by the Char tered Institute of Personnel and Develop ment (CIPD). According to the CIPD, it is not so much the workplace that poses a problem in terms of collective innovation as the team processes that have to be designed to facilitate coordination and communication between their members. It cites a global study of 80 software development teams in 28 labs around the world59. Teams that introduced such processes consistently outperformed other teams, whether they were collocated or working remotely. The study points out, on the one hand, that dispersion can be very diverse in nature and that on-site distance (between floors) can have more negative effects on a team’s effectiveness and efficiency than geographical distance (see Chart 2.3). On the other hand, dispersed teams have positive effects on innovation, bringing together a diversity of expertise and creating cultural heterogeneity that can multiply perspectives (while lowering costs). To take advantage of this diversity, however, a specific management style needs to be adopted: optimising task-related processes (balanced distribution of tasks, coordination, mutual support, formal communication), while supporting socio-emotional factors (team cohesion, identification and informal communication). The testimony of a Grenoblebased executive producer from Ubisoft, who was interviewed for this study and who manages teams of 800 people spread over all the continents for the development of new video games, has the same thrust60.

Thus, collaboration does not only take place through collocation. It needs to be thought out, formalised and explained. As the CIPD concludes, “innovation depends on good relationships and good knowledge sharing. Employers might do better to focus on these rather than on where people work”.

Finally, it is worth noting that 25% of managers in France felt that creativity had increased since their team started working remotely at the end of 2020, and 54% of remote workers said they felt they had a greater capacity for innovation when working at home61. This makes the picture even more confusing!

In the end, the impact of remote working on innovation and creativity remains one of the most important and controversial issues, and one that the 2020 experience has not settled. Before resigning ourselves to the fact that remote teams cannot be creative, it would seem important to try out new things – in terms of methods, management styles and digital tools (see also Chapters 4 and 5).

Chart 2.3 Work team performance according to location

How to read: Teams located in the same building on different floors perform less well in terms of effectiveness (quality of the result in relation to the objective set – grey curve) and above all efficiency (quality of the result in relation to the resources invested – yellow curve) than teams dispersed over a city/country/continent because they underestimate the obstacles to communication and neglect collaborative processes due to physical proximity between individuals.

Source: Siedbrat F., Hoegl M., Ernst H., “How to manage virutal team?”, MIT Sloan Management Review, 1 rst July 2009.

What impacts on quality of life at work and psycho-social risks?

In terms of quality of life at work and the rise of psycho-social risks, the suboptimal conditions under which workers worked from home during lockdown do not allow us to draw lasting and general lessons. However, they do help to draw attention to aspects of working from home that can have a negative impact on quality of life at work, in the event that new and now entirely conceivable circumstances (new health crisis, but also general strikes, pollution peaks, extreme weather conditions, civil unrest) once again bring about the need for remote working on a large scale. They also highlight areas that need attention for the establishment of high-quality conditions for remote work.

Among the negative effects of continuous remote working on quality of life at work, employees are particularly concerned about the following.

• The intensification of work time and workload mentioned earlier (see above Productivity). This is often coupled with shorter and fewer breaks and less physical activity, as working from home encourages a high level of sedentary behaviour. Working from home can thus result in overwork (workaholism) at the expense of the remote worker’s personal and social activities (taking care of oneself, resting, practicing leisure activities or going out). This can lead to symptoms of fatigue, anxiety and even burnout. This phenomenon has affected both non-managerial and managerial employees who worked from home in 2020.

• Social isolation is a factor in the perception of work-related stress and can be related to the fear of missing out on professional opportunities.

• Lack of information provided by supervisors (job objectives, evaluation criteria) and lack of equipment and digital training. This was particularly glaring during the first lockdown which took place without any preparation.

• Difficulties in being heard and / or consideration of the difficulties encountered. A lesser sense of belonging and less identification with the organisation.

For all these reasons, remote working is often associated with the development of psycho-social risks, which were greatly intensified with forced working from home during the public health crisis, whilst the pandemic itself provoked a great deal of anxiety. Apart from psychosocial risks, the ILO states that working from home also increases physical health risks: musculoskeletal disorders (MSD), eye strain, obesity, heart disease, etc.62

MSD is obviously related to the ergonomics of workstations, which was clearly lacking in 2020 due to the lack of preparation for the transition to from-home. Studies show only 50% of remote workers had good workstations at home, with 21% admitting to working from their dining tables, 12% from their sofas and 4% from their beds63.

Physical problems, then, become increasingly common with from-home: eye strain, back pain, headaches, stiff neck. Osteopaths and physiotherapists are seeing a huge increase in consultations. A sedentary lifestyle is also an issue: an ONAPS (French National Observatory of Physical activity and the Sedentary Lifestyle) survey shows that during the 1 st lockdown, 25% of adults increased time spent sitting and 41% increased screen time. Physical activity also decreased significantly, with the cessation of all sorts of daily journeys and the closure of gyms. This will potentially have disastrous effects further down the line, since a sedentary lifestyle doubles the risk of cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity64.

International comparisons on quality of life at work for home working during lockdown

The findings are similar in other countries around the world.

An anonymous survey of tech professionals in North America65 showed that 73% of them said they were exhausted at the end of April, 12 points higher than in February. For 20.5%, this exhaustion was due to higher workload.

A London Business School survey of 3,000 people during the 1st lockdown66 found that the biggest concern for home workers was a lack of social interaction (cited by 46% of respondents). 62% of respondents in a global survey of 11,000 workers in 24 countries said working from home was socially isolating. According to the same survey, 50% feared that working from home would reduce opportunities for promotion. This fear is both confirmed and put into perspective by another study of 405 American remote workers: promotion opportunities are most restricted when working from home full-time.

In terms of negative physical impacts, the findings are just as worrying as in France: eye strain (41% of remote workers, the same as in France), headaches (39%, 8 points more than in France), back pain (37%, 2 points less) and neck stiffness (30%, 8 points more). Fifty-two percent of them said that their home workstation is the cause of more pain than the office one (2% more than in France) and 71% have had to equip themselves without material or financial assistance from their companies (6% up on France)67.

It would therefore appear urgent to integrate the specific risks related to remote working in company occupational riskassessments but the regulations remain un clear. While European Directive 90/270/EEC obliges employers to conduct regular risk assessments for office workers and for permanent home workers, the guide lines concerning temporary home workers are less clear.

However, if we isolate the risk factors that are mainly related to 100% remote working itself, then the benefits of remote work in terms of quality of life at work are clearly perceived by the employees, as long as companies take some precautions.

The reduction of micro-interruptions by colleagues and managers reduces the perception of work-related stress. This suggests that managers should be careful not to require remote workers to respond in real time to digital or telephone requests.

Flexibility in working hours means employees feel more in control of both their time and their working methods. This presupposes that Trusted Work Schedules (TWS) exist, which goes hand-in-hand with a results-oriented type of supervision (see Chapter 4). The OECD observes that TWS can be seen as a prerequisite for home working. “The company gives up control over the working time of its employees and evaluates their performance solely on the basis of their output. As a result, companies that use TWS are more likely to adopt home working.68” As long as from-home remains the choice of the worker and is intermittent (or hybrid), it is likely to “increase feelings of independence, motivation at work, organisational involvement and job satisfaction”69. All these factors have an impact on quality of life at work and result in a lower rate of absenteeism, a lower level of intention to leave and a lower turnover rate. However, these beneficial effects presuppose that material, organisational and personal conditions are met (see Chapter 3).

Accommodating or destructuring social time?

This is the argument most often put for ward in favour of remote work: that it allows better accommodation of people’s social time, thanks to the time saved in transport, greater flexibility and greater selfcontrol, allowing people to better organise their multiple roles and activities (professional, family, friends, leisure). Isn’t there a risk however of seeing the destructuring of social time and work absorbing all of life’s time?

The ability to compartmentalise the professional sphere from the private sphere at home and to establish clear spatial and psychological boundaries for each is not innate. These are practices that take place gradually and take time. Freelancers and other self-employed people are very much aware of the problem, working in cafés (when open!) or booking a place in a coworking space, not so much to escape isolation as to separate off the different parts of their lives.

Work done at home tends to overflow into other activities, with a risk of overwork that ends up absorbing all life’s time. Remote workers “express difficulties in containing work and stopping themselves from being invaded by it”70. This results in misunder standings, tensions or conflicts with family and friends, as well as an increase in stress in the private sphere, both from the remote worker’s point of view and that of the people around them. The first lockdown thus highlighted the unfavourable situation of women, who are still responsible for most domestic tasks which cause a high cognitive load. The lockdown increased childcare and homeschooling responsibilities. This may partly explain the significant increase in separations and divorces in 2020, especially those initiated by women. Difficulties in coping with the demands of work and family and in responding to the demands of family and friends mean that home-based workers report feeling a great deal of pressure and often sacrifice the time they would like to spend on rest, leisure or going out – an issue that was exacerbated in 2020-2021 by the scarcity of entertainment opportunities during the pandemic.

Testimonies from managers, and more particularly female managers, confirm this point. Emily, for example, says how much she misses moments of transition or times when she can decompress, for example the “just for me” time spent in the car with her music. Currently, as soon as she closes the door to her home office, she goes to the kitchen where hungry little mouths are waiting.

Finding solutions to these problems requires the development of new behaviours, rules and personal rituals, which also need to be negotiated with family or people around, leading to the sharing of tasks and consideration of the rhythms of the day. Having a room at home reserved for work – “a room of one’s own” as Virginia Woolf said – with a door that closes, is obviously an advantage. At the end of the day, one closes the door to one’s “office” and leaves work behind.

Because many workers, especially executives, are also generally “addicted” to their digital devices, there are more and more applications to help them discipline themselves and develop a more rational use of these devices. These applications can range from simply measuring the time spent on the Internet, one’s mailbox or social net works (to increase awareness) to blocking devices when the time counter set by the user is reached. By using this type of ap plication, managers can set an example on how to introduce the right to disconnect.

The intrusion of professional life into the private sphere also manifests itself through the use of videoconferencing, an open window on the home and personal image of each individual. This explains the use of wallpapers or cameras that are turned-off. Video conferencing can indeed become an indicator of inequality if employers oblige employees to turn the camera on – a le gally questionable practice with regard to both the GDPR and labour law. However, on the positive side, the intrusion of videoconferencing into the private sphere during lockdown also made employees realise that their local managers often lived like them and shared similar problems: no dedicated office, small children who wave at the camera, pets, etc. This mirror effect helped break down barriers and create closeness and bonds, which help create a climate of trust for the future.

Companies can obviously help in separating off social time or, on the contrary, create conditions that are counterproductive. Respect for the right to disconnect and tolerance to asynchronous response times (see Chapter 5) are positive as are the organisation of meetings and discussions during normal working hours and during periods set aside in advance for such activities, one-to-one (or bilateral) discussion time between managers and non-managerial employees to explore issues other than just work, ergonomic and health advice guides for home working (take breaks, eat well, get up and stretch regularly, go outside, drink water, etc). Part of this effort to regulate work also depends on the employee’s ability to self-manage his or her work activity, to set goals, structure the working day, prioritise tasks, manage time, etc. This implies having reached a certain level of independence at one’s work activity. The sociologist Jean-Luc Metzger points out that, in so doing, the burden of supervision is now entirely transferred to home workers and their families, with families constituting “the main safeguard against overwork”71. In essence, he highlights “the existence of a void in regulating between the professional and private spheres, a void that companies create by shifting responsibility for learning to regulate onto individuals, after having made it invisible”.

When all these concerns are taken into account, remote work can then have positive impacts in terms of the work/life balance and mutual enrichment of both work and non-work.

International comparisons on work-life balance

flow into other activities, with a risk of overwork that ends up absorbing all life’s time. Remote workers “express difficulties in containing work and stopping themselves from being invaded by it”.

This ambivalence is also found in other countries. A study conducted in Germany in 2013 showed that 79% of the 505 employees surveyed considered that working from home helped them to reconcile work and family life, while at the same time 55% regretted an excessive overlap between these two spheres.72