Voyage into Italy’s industry of the future

This publication is the result of a journey to visit a sample of Italian companies, starting in 2014 and ending in spring 2016.

After an erratic start, Industry 4.0., and digital transformation in general, is high on the agenda in all major European countries. Several reasons explain this interest: one is the urgent call on governments to provide national industries with concrete tools to tackle a paradigm shift that was becoming difficult to ignore; the other is the role played by social partners, universities, business support organizations and think tanks in raising the alert about the changes underway – changes that would have come about with our without public support policies.

Although this debate can be too theoretical, and sometimes too prospective, it nevertheless has several merits, including: putting the spotlight on the European manufacturing sector as the central driver of our economies; drawing attention to how slowly our businesses have been adapting to technological innovation; and underlining the urgent need to seriously reflect on the future of labour and social protection.

Within the European debate, the discourse on the industry of the future is slightly different in France. The talk is of open innovation, now considered as a powerful mechanism for taking digital innovation to the heart of business, and right into the structure of national industry to profoundly change it. It is this unusual vision, or strong stand, that attracted the interest of Inwibe for the subject that we tackle here.

Unlike major companies equipped with significant financial and industrial capacities, SMEs cannot take on digital innovation with the conventional perspective of a return on investment. This obviously does not mean that disruptive technologies and methods like open innovation are reserved to large operators; on the contrary, industry will only be truly transformed when digital equipment has been introduced and adopted by small firms and when open innovation has become standard, common practice.

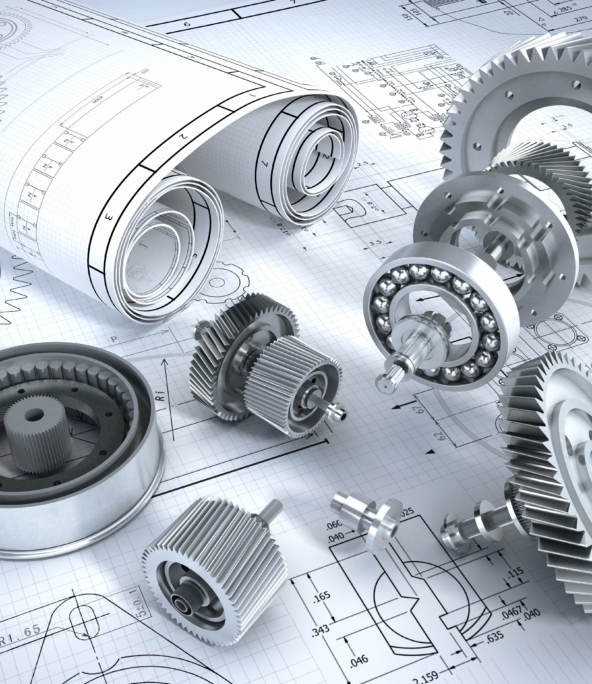

A small-scale model involves working on highly tangible projects of a limited size and taking an evidence-based approach. The focus should be on concrete action that can quickly generate economic returns to match the investments made. Such projects are ideally suited to factories because they feature a complex orchestration that involves getting physical groups, high technology, digital solutions and, last but not least, people, to work together – and all synchronously to successfully achieve transformation.

Whatever the national course chosen, in view of the wide range of industrial and tax policies to support businesses, the industry of the future cannot be considered as a local issue. You only have to look at the map of the digital single market posted on the European Commission’s web portal and featuring the different active programmes to get an idea of the importance of a transnational approach.

Our research, based on a sample of factories located in Italy, takes this perspective: the companies, which we approached with a field survey method, belong to multinational groups, representing various activity sectors and different cultural backgrounds – French, German, American, etc. Each of these factories in the process of 4.0 transformation has its own characteristics, but also a number of common features, precisely because technological and organizational innovation, business rationality and the meaning of human work know no borders.

The companies that we focus on in this work are large, sometimes very large, and as such do not represent typical Italian companies. At the time of publication of the French edition, Torino Nord Ovest is finalizing a new phase in this research, this time targeting homegrown Italian SMEs. The reason is that, according to many observers, they are the real backbone of the Italian production system, i.e. internationalized SMEs situated in value-added niche markets. They are also affected by the wave of digital transformation. Nevertheless, as this present study shows, the characteristics of an Italian-style industry of the future can already be identified, i.e. the importance of production channels; the digital adaptation of business management tools; and automation and robotization choices aimed at improving product quality rather than producing bigger volumes.

***

This publication is the result of a journey to visit a sample of Italian companies, starting in 2014 and ending in spring 2016. Well before the launch of the Impresa 4.0 plan, also known as the Calenda Plan after the minister who conceived it, these companies had already embarked on the paradigm shift triggered by Industry 4.0 in terms of technological and cultural changes. They were looking at the implications of a shift that concerns how industrial goods are designed and how we work in factories and offices. A shift that also concerns the relationship between humans and robots, and the design of more flexible, sustainable, ergonomic and intelligent factories, i.e. smart factories. Lastly, a shift that concerns the relationships between companies, because this transformation starts by affecting major companies and then progressively filters down to small and mid-sized companies, and changes value and supply chains and the professional skills required to work in them.

Faced with this fast, deep-seated change, supported by significant European funds, how, given its specific characteristics within the international division of labour and globalized value chains, can Italian industry take on the digital revolution? To answer this question, we have taken the particular angle of not just looking at technological potential, or economic results, but the change in work processes within factories. What transformations can already be seen? What adaptations? What can we anticipate for the future? In a nutshell, this book recounts Industry 4.0 through those implementing it and those who manage its effects.

The academic literature provides little support on this theme, often only dealing with the question of labour in smart factories in an extremely general, theoretical way. There is a big gap between the abundant analyses of smart production and those relating to the work conditions involved. Consequently, we have chosen to take the opposite view, i.e. to look at the silences, questioning what neither the literature nor even the interviews tell us, or only partially tell us, going beyond the testimonials of our interviewees and those working in management.

In fact, the signs of factories’ technological and organizational revolution, largely debated in the economic literature, academia and the media, were only perceptible in a few of the companies that we visited or in some of their departments, although a transversal, diffuse move towards “smart production” is certainly under way. The intensity of the changes taking place is very different depending on the sector and the company. This observation shows the need to go beyond the unique character of individual factories and look at production channels, which are themselves very different from each other.

The cases examined feature a wide variety of products and markets. They include major companies in the automobile, engineering, shipbuilding, chemical, energy, electronics, robotics and advanced components industries, or in services to industry (logistics or research). These set-ups have very different statuses depending on the type of company that they belong to: single, independent establishments, leaders of industrial channels, multinational subsidiaries, and Italian groups. The production characteristics of these factories are specific to their activity sector: unique parts to order, limited or wider-ranging series, services to industry. Nevertheless, none of the establishments visited are truly representative of mass production. Lastly, these factories are at different stages of maturity concerning the integration of new technologies.

This sample does not therefore set out to represent the entire Italian production system. Nevertheless, due to its diversity, it provides a means to evaluate where and how the “smart factory” paradigm is filtering into Italian industry, and whether it constitutes a strong trend for the country’s industrial future. Due to their exploratory character, the aim of the reflections that follow this “journey into factory country” is not to make any conclusions, but rather to provide some useful pointers to continue research on factories and Industry 4.0.

To order the Note in paper version, please go to the Presses des Mines website.